Interagency Collaboration

Our current rate of drastic planetary climate change means that there is a need to efficiently tackle environmental problems and restructure existing systems, like transportation and energy, to be more sustainable. To that end, it is important that organizations and individuals working on environmental sustainability projects are able to complete their work as efficiently as possible, such as by joining forces with others working towards the same goals. There has been growing acknowledgment of the importance of interagency collaboration for improving community well-being, environmental and public health, and education outcomes, among other benefits. [1] Interagency collaborations are valuable for expanding the reach of services, minimizing costs, sharing expertise among stakeholders, strengthening democratic processes in the public sphere, and empowering community members through relationship building and achieving goals. [2]

[1] Cross, Jennifer Eileen, Ellyn Dickmann, Rebecca Newman-Gonchar, and Jesse Michael Fagan. 2009. “Using Mixed-Method Design and Network Analysis to Measure Development of Interagency Collaboration.” American Journal of Evaluation 30(3):310–329.

[2] Johnson, Lawrence J., Debbie Zorn, Brian Kai Yung Tam, Maggie Lamontagne, and Susan A. Johnson. 2003. “Stakeholders’ Views of Factors That Impact Successful Interagency Collaboration.” Exceptional Children 69(2):195–209.

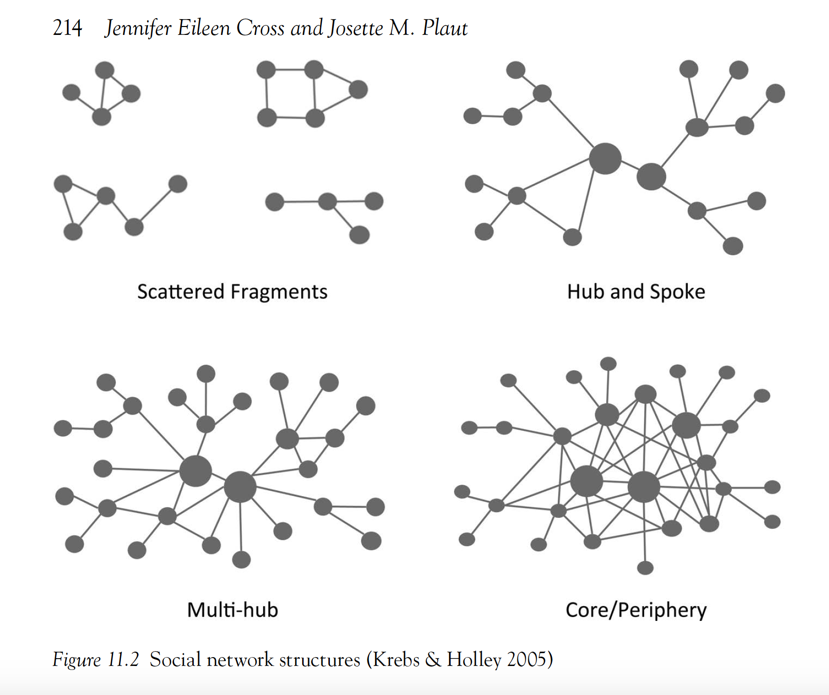

The academic literature suggests that sufficient resources, pre-existing social networks, trust, acceptance of leadership, and a flexible and adaptable approach can all increase the successfulness of interagency collaborations. [3] Social network structure and the strength of relationships between network members also play an important role in achieving desired outcomes of collaboration, such as knowledge sharing, organizational change, productivity, and innovation. [4]

[3] Bardach, Eugene. 2001. “Developmental Dynamics: Interagency Collaboration as an Emergent Phenomenon.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 11(2):149–164.

[4] Cross, Jennifer Eileen, Ellyn Dickmann, Rebecca Newman-Gonchar, and Jesse Michael Fagan. 2009. “Using Mixed-Method Design and Network Analysis to Measure Development of Interagency Collaboration.” American Journal of Evaluation 30(3):310–329.; McEvily, B., V. Perrone, V., and A. Zaheer. 2003. “Trust as an organizing principle.” Organization science, 14(1), 91-103.; Reagans, R., and B. McEvily. 2003. “Network structure and knowledge transfer: The effects of cohesion and range.” Administrative science quarterly, 48(2), 240-267.; Granovetter, M. S. 1973. “The strength of weak ties.” American Journal of Sociology 78(6): 1360–1380.

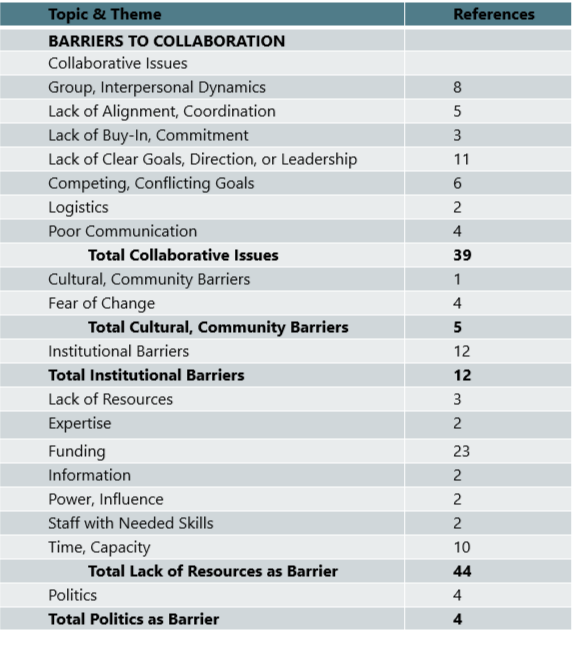

Word cloud of barriers to collaboration reported by Fort Collins Environmental Sustainability Network members

The difficulties of establishing interagency collaborations across sectors—i.e., between governmental, non-profit, for-profit, and educational entities—have been noted by many researchers. [5] Some typical barriers to interagency collaboration include lack of understanding of other agencies’ policies; lack of communication; lack of time and funding; unclear goals and objectives; gaps in services that identify needs; inconsistent service standards; excessive use of jargon; conflicting views and values; bureaucracy; collective decision-making; and resistance to change. [6] Sound familiar? If so, read on!

Barriers to collaboration reported by Fort Collins Environmental Sustainability Network members

[5] Guo, Chao and Muhittin Acar. 2005. “Understanding Collaboration Among Nonprofit Organizations: Combining Resource Dependency, Institutional, and Network Perspectives.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 34(3):340–61.; Seibel, W., and H.K. Anheier. 1990. “Sociological and political science approaches to the third sector.” The third sector: Comparative studies of nonprofit organizations, 21(7).

[6] Johnson, Lawrence J., Debbie Zorn, Brian Kai Yung Tam, Maggie Lamontagne, and Susan A. Johnson. 2003. “Stakeholders’ Views of Factors That Impact Successful Interagency Collaboration.” Exceptional Children 69(2):195–209.; Friend, M., and Cook, L. 1996. “Interactions.” Collaboration skills for school professionals. 2nd ed. White Plains: Longman; Pugach, M. C., and L.J. Johnson. 1995. Collaborative practitioners, collaborative schools. Denver: Love Publishing Company.; Stegelin, D. A., and S. Dove Jones. 1991. “Components of early childhood interagency collaboration: results of a statewide study.” Early Education and Development, 2(1), 54-67.

Examples of network structures.

Source: Krebs, Valdis and Holley, J., 2005. “Building adaptive communities through network weaving.” Nonprofit Quarterly, pp.61-67.

Given the potential to experience barriers when attempting to engage in an interagency, cross-sectoral collaboration, it is important to understand the structure of the social networks within which people and agencies are operating. Social network structure plays an important role in facilitating the flow of resources, development of trust, and alignment of values and priorities that are needed to overcome the many potential barriers to collaboration. [7]

And that’s where social network analysis comes in! Social network analysis reveals the structure of social networks, allowing us to make inferences about how resources flow throughout a network, to predict the collaborative strength or weakness between specific actors, and to understand the gaps and needs of the overall network to improve its cohesiveness and ability to function.

For more information about social network analysis, please see the “Data” section.

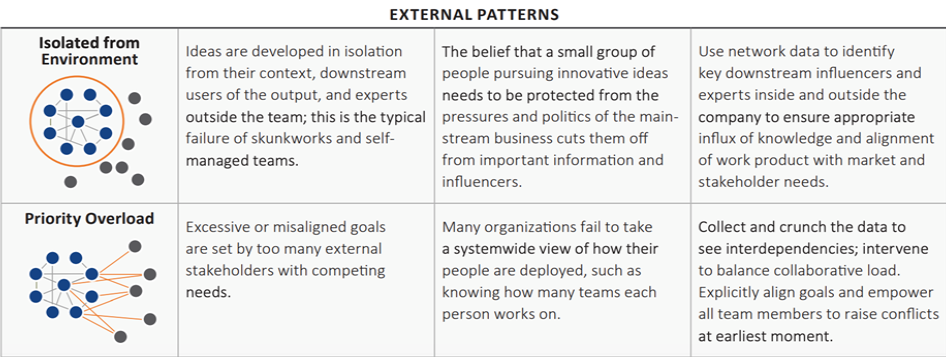

How network structure affects efficiency.

Source: Cross, Rob, Heidi Gardner, and Alia Crocker. 2019. “Networks for Agility: Collaborative Practices Critical to Agile Transformation.” Connected Commons.